Apple, iPhones, and Demand Curves, and “Price Discrimination”

After some thought, I have decided to write about what Apple did right, and wrong, in their decision to lower the prices on the iPhone. Essentially, I believe they recognized the opportunity to generate more revenue from a lower price point, and chose to practice price discrimination to achieve that. Alas, they made a couple significant mistakes. If you read to the end, you will see what those mistakes were.

I think it is time for another look at that old friend of Economists and students in Econ 101, the “Demand Curve” and the slightly more complex notion of “Price Discrimination.”

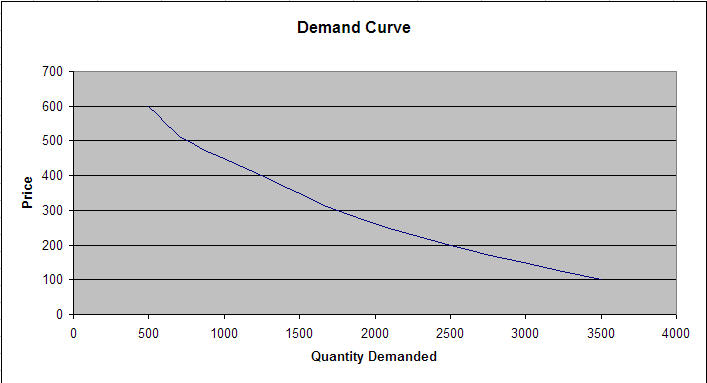

To catch up, you undoubtedly recall that the demand curve essentially shows that, as prices decrease, demand will increase for a product. This is shown in the following graph:

Thus we can expect Steve Jobs is correct in saying that they did this to increase sales before the Christmas season. In fact, lowering the price should increase the sales, assuming that there is elasticity in the pricing and demand curve. Remember, elasticity is the degree to which quantity changes with a change in price. The more elastic, the greater the change (steeper the slope of the curve.)

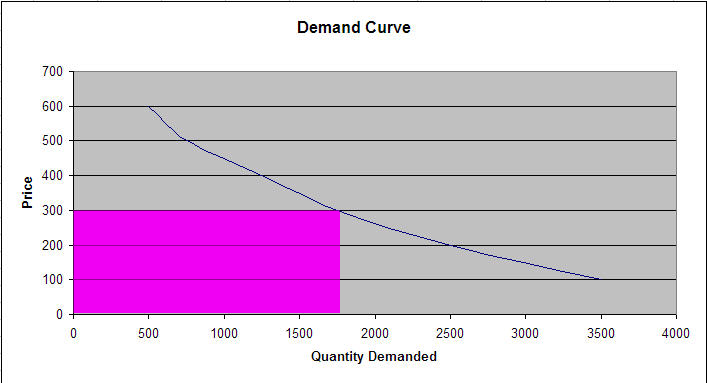

Now, there is this other notion of “price discrimination.” Price discrimination, or “Yield Management,” is the practice of charging different customers a different price for the same product. The notion is really quite simple. As we saw in the Demand Curve, a few people are willing to pay a high price for a product. A few more would be willing to be a lower price, and so on. In the charts that follow, one can see how, by targeting different customers at different prices points, one can increase total revenue.

The first chart shows the revenue generated if one were to charge a single price. You can see that above the “box” is the revenue that is essentially lost due to customers getting a “good deal.” They would have paid more, but are most likely happy that they were able to pay less. Of course, to the right of the “box” is revenue lost because customers felt the price was not at a point where they could make a purchase.

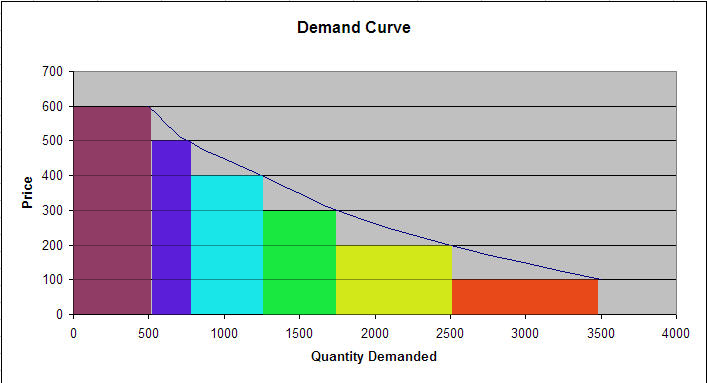

This next chart shows, notionally, what would happen to revenue if a business were able to successfully segment the market, and provide 6 different price-points. As you can see a far greater area under the curve is colored in, showing a significantly greater amount of revenue.

By identifying these customers, and finding ways to segment the market, a business can capture more revenue by charging higher prices to those willing to pay those prices. Ideally, businesses would like to charge a different price for every customer, targeting the maximum price they are willing to pay. That level of price discrimination would ensure that every customer felt they were receiving a “fair” deal, while removing even the smallest gaps between revenue and the demand curve. This is rare, although an argument could be made that we see this in online auctions and in car sales with negotiations.

Realistically, we do see price discrimination in our daily lives. Customers can find the “same” available for different prices, simply by shopping at different stores. What makes people pay more? A sense that they are receiving something additional for the increased costs. We are perhaps most familiar with this practice in the airline industry, where yield management has gone from art to science. We pay more for a first class ticket (obvious difference in treatment, although you still arrive at the same destination.) But customers also pay a higher price for the privilege of changing travel arrangements, or for the ability to purchase tickets at the last minute. Alternatively, the airlines are able to ensure full planes by offering a select (and scientifically computed) number of seats at lower prices. Travelers must purchase these tickets within certain guidelines, but more tickets are sold (and seats filled), because they are able to capture those people who could otherwise (perhaps) not afford to travel.

If you look around, you can find other instances as well. Coffee is more expensive depending on whether a coffee shop has the right “feel.” Clothing is more expensive when purchased at “higher end” stores.

What is critical here is the ability to segment your customers, and by doing so, create barriers to transfer. This can be accomplished in many ways to include rules ( in the airline and cellphone industries), controlling information (automobile industry), perception of enhanced service (coffee shops and boutiques) and through geography (different shopping “districts.”)

So what does all this have to do with Apple?

I am glad you asked. I believe Apple made a “good call.” They sought to capture as many people in the high end of the Demand Curve as possible. The problem (if you believe that sales may have been trailing off in August) is that the demographic may have been smaller than they anticipated, or they all reacted more quickly purchasing en masse early on. This then left a potentially large amount of sales untapped. This is essentially what Steve Jobs was talking about when he kept referring to capturing the holiday sales. They want to increase sales and to do that, they must change the price point. This slides them down and to the right along the demand curve.

I suggest that Apple was trying to practice what I will call “temporal price discrimination.” They were hoping to capture the “big spenders” early, and then move down the curve, capturing sales from those who could not, or would not, spend at the higher price points. Unfortunately Steve Jobs misjudged the timing. The group that purchased the iPhones at the higher prices were not satisfied to say that 30 to 60 days of use of an iPhone was sufficient differentiation in their minds to have paid a higher price. For many, one could argue it wasn’t worth $100 to $200 per month to have a cool phone.

So, Apple failed to take the necessary steps to successfully practice price discrimination. They failed to differentiate and segment their customers in a significant and substantial way. They did try to create barriers. They were going to limit the number of people that could “switch”1 to the lower price by putting a time window on when you could get your money back. But customers, apparently in droves, pressured Apple early and often. Jobs responded within 36 hours, offering in store credit (among other reported compensations.)

All in all, I think this has been an interesting time. I have only given a cursory look at the economics involved, and there are far more details I left out (did I forget to mention marginal costs?)Â Also, I am sure there are many other factors and pressures that influenced Apple’s initial decision, and some may even include a pending shift in the demand curve itself. (If new technology makes customers feel this iPhone Gen 1 is “obsolete” then the whole demand curve might shift to the left…) Perhaps we shall revisit this topic…

1 Ironic that, eh? Apple trying to stop people from switching?

Pingback: More Apple Price Discrimination « Scientific Pornography