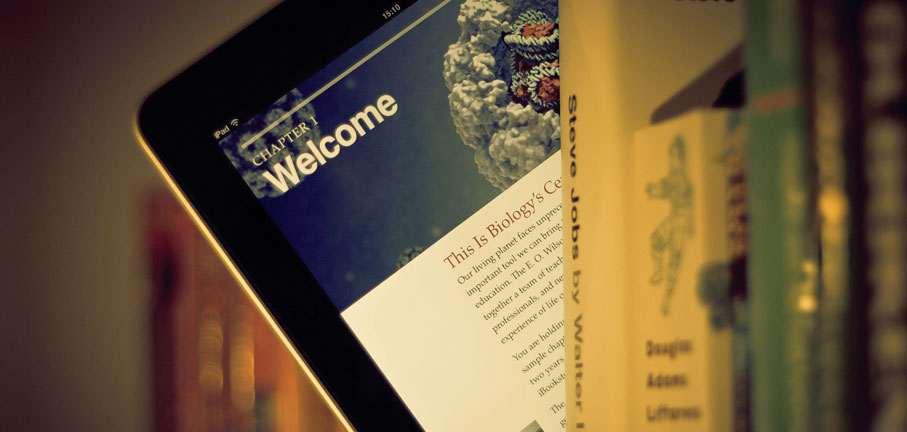

Digital Textbooks and “Fair Pricing”

Those who know me personally know I have a strong desire to see digital textbooks succeed. I think it has the potential to deliver a Win-Win for most of the major stakeholders, including the authors, the publishers, the environment (potentially) and the students.1 Perhaps the biggest challenge facing everyone in this is how to achieve that “win-win”and this involves a mix of pricing, availability, and convenience. I hope to address that in this post.One of the most consistent, and loudest, complaints I have heard from students has been that textbooks are “outrageously priced.” It’s hard to argue when students are paying $150 to $200 (and sometimes more) for their textbooks. Unfortunately, those prices are all to easily justified by the publisher when the remind us of

- Text books have a limited audience, resulting in smaller volumes of sales and prin runs (10’s not 100s, of thousands). Limited runs mean that the overhead and setup costs of printing a run are spread across a fewer number of books. Historically to make a book cheaper they either had to reduce the quality of the materials, automate the process, or produce larger production runs hoping to sell more of the books.

- The costs associated with distributing books are high (packaging, warehousing, and shipping to name a few key ones)

- The inability to accurately forecast demand for “new” editions at locations, because of the…

- Strong used book market that publishers compete against

My support for digital textbooks has emphasized that digital textbooks drive out out the costs associated with physical books, and thus allow for both a reduction in price, and an increased margin for the publisher. This can be seen because:

1. Publishers no longer need the overhead necessary to design the packaging (including the covers), presses to print the books, warehouses to store the books, or distribution systems to ship the books.  Oh, and they don’t need the management to manage all of that. This drives costs out of the process. (hint–what could this do for prices?)

2. Because the books are delivered, directly to the student through digital means, there is no need to keep safety stocks of book inventories to cover the sales of the books. No physical inventory drives costs out because it means there is:

- No capital outlay for bookstores to buy a “forecasted” amount of books

- No shelves required for the books

- No possibility of stockouts (I had a class where there were only enough books for 10% of my students well into the second week of class!)

- No need to ship back the unsold books, because the forecast was “wrong” (due to used book sales, borrowed books, or just students “dropping” the class.)

3. The digital rights management (DRM, or “copy protection”) of digital books appears to be rock solid, so students are not likely to “give” copies to their friends. Publishers would be guaranteed sales2, allowing them to lower prices. This would mean that:

- Publishers don’t compete with a ‘re-sale’ market. Think about this. Part of the reason the costs are so high for the textbooks is that the publishers know that they will only “fully” sell out in the first semester the book is available. Every semester after that they are competing with a (rather robust) resale market.

- Publishers won’t have to release new editions every two years “simply” to refresh the sales. With strong DRM publishers can expect to make sales to nearly every student, every semester.

- New editions will be developed for the right reasons–new, improved content and new knowledge.

Given the above, my argument really focused on the need for publishers to pass on the savings to the consumer (the student) making textbook pricing reasonable again.  The major criticism of students (the high prices of textbooks) could all but disappear.

Affordable textbooks for students, and increased (and guaranteed) revenue for publishers!

One of the key points in my argument had been (yes, had) that the DRM on the Kindle and Sony readers was secure, and thus students wouldn’t hack the books and “share” (illegally give copies) to other students. That is essential to keeping the revenue model moving forward for publishers and is why the RIAA and MPAA are working so hard to protect their intellectual property. But alas, sometimes things change, and we know that if anyone can hack a DRM it will most likely be motivated college students.

Thus, I have been spending time thinking about how we can still achieve a win-win, even if students “crack” the DRM market.

Stay tuned! More on this to come!

1 Unfortunately, there will be near term losers, including the people working at the printing presses, the local bookstores, and the supply chain partners that normally deliver, store, and reship textbooks. More on these folks later.

2 Think about it. In a class of 30 students, in the first semester a new book is offered, all the students will buy the book. Let’s say the book costs $100. That is $3000 in sales for the publisher. (Not profit. Remember the high costs of physical books.) Now let’s assume that half of the students with new books decide to resell their books each semester. If in the next semester half of the next class purchases “used: books that reduces the revenue for the publisher to just $1500. If we follow this through, then the 3rd semester, 3/4ths of the books in the class are used books cutting revenue to $750. by the end of the second academic year the publishers revenue is cut to about $400. In two years, with 120 students going through the class, the publisher would make $5650. If there was no used book market, the publisher could make the same revenue selling the books at $47/book. And that is assuming there was no savings in costs by shipping digitally!

That’s exactly why digital books ARE the future. One college is already trying them

Rick

Pingback: The Professor's Notes » Blog Archive » Digital Education Resources: What price, adoption?